Entertainment

Camping

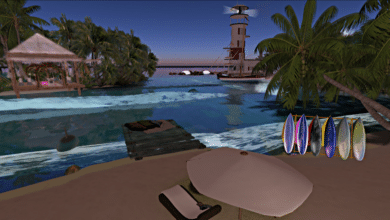

Landing Mark

Camping is when somebody pays you to sit (or dance, or sweep the street, or wash the windows …) at their land; the longer you stay the more you earn. Typical rates are L$1 per some variable minutes. At today’s exchange rate.

Camping typically happens in shops, malls and clubs. Don’t feel too bad about camping, though: everyone has done it for some amount of time, at least when they were newbies.